|

|

| Photography in Flux 1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018 |

|

|

|

| Should I Do a Photography MA? Source 91, Autumn 2017 |

|

|

|

| Expanded Photography: Persistence of the Photographic PhotoResearcher 26 (2016) |

|

|

|

| Poetic, Magic (Book Review) Source 85, Spring 2016 |

|

|

|

| Situations and Seductions: Mariana Rothen’s Shadows in Paradise Photoworks Annual 22, 2015 |

|

|

|

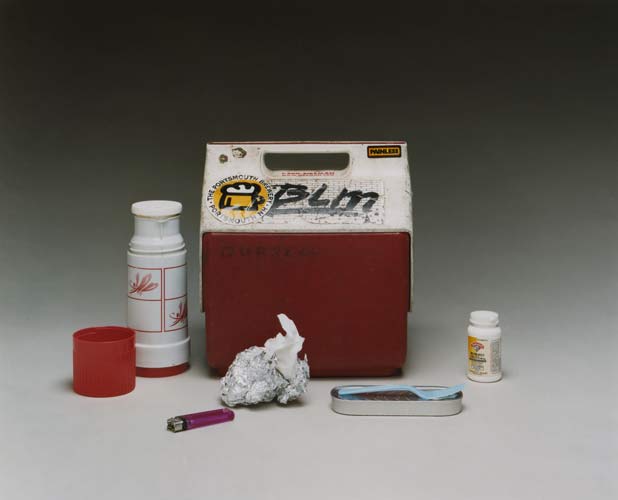

| Conceptual Photography Source 71, Summer 2012 |

|

|

|

| Perhaps When Reproduced Language and Site in Lawrence Weiner's Public Freehold Works ARC14, Summer 2010 |

|

|

|

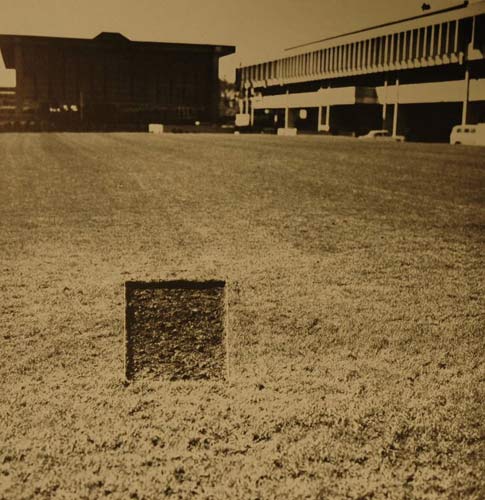

| Idris Khan: The Collapsed Archive Source 49, Summer 2006 |

|

|

|

| Karen Knorr: Fables Portfolio 42, December 2005 |

|

|

|

| Adam Fuss: Medium as Muse Source 45, Winter 2005 |

|

|

|

| Malerie Marder: The State of Contemnporary Desire Source 44, Autumn 2005 |

|

|

|

| Hannah Starkey: Art's Best Tricks Source 40, Autumn 2004 |

|

|

|

| The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography Afterimage vol. 26 no. 5, March/April 1999 |

Portfolio 42, December 2005

The Thirsty Pigeon

A pigeon, oppressed by excessive thirst, saw a goblet of water painted on a signboard. Not supposing it to be only a picture, she flew towards it with a loud whir and unwittingly dashed against the signboard, jarring herself terribly. Having broken her wings by the blow, she fell to the ground, and was caught by one of the bystanders.

Zeal should not outrun discretion. 1

Fables are due for a revival. Short, pointed narratives, peopled with familiar animals and barbed with cruel morals, they explore the myriad facets of human vanity. They seem particularly well suited to our own era, with its decadent consumption, spectacularity, and highly developed taste for shadenfreude . Fables have been used since ancient Greece to consider the baser aspects of human nature. Writers and artists from Jean de La Fontaine to Charles Schulz have drawn on Aesop's legacy to skewer specific politics or attitudes of the day. And certainly, many of Aesop's morals ring true to our own moment, not least "Familiarity breeds contempt," (The Fable of the Fox and the Lion) "One bad turn deserves another," (The Fox and the Stork), or "Any fool can despise what he cannot get" (The Fox and the Grapes).

Karen Knorr's most recent series is entitled Fables , but the morals of the individual images are not immediately apparent. The colour Lamda prints, staged in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris, feature classic animal characters: the cunning fox, the foolish pigeon, the parsimonious squirrel and the pesky rat. Yet these creatures--borrowed from a taxidermist's shop rather than a zoo--are not doing much to move a narrative along. Rather than earning some kind of humiliating comeuppance, these intruders are mostly sitting or standing quietly. Their gazes draw us into the highly loaded recessive space and provide an allegory for the way we look at this strange rarefied world of culture and at the photographs themselves.

Knorr punctuates her elegantly composed period interiors with details that jar us back to the present. In various Fables we can see an illuminated exit sign, wall labels, and contemporary track lighting. These details provide the clues that these images are not supposed to represent some kind of time-travel to the original incarnation of these rooms. Rather, we are in a time apart, an imaginative time/space parallel to our own, akin to the subversive scenario in which the nursery toys come to life after the children have gone to bed.

In Demarteau's Study , three rats and a grey squirrel occupy a remarkable Rococo room the walls of which are painted with pastoral and farmyard scenes. While one rat concentrates all his attention on the floor, the other two stand upright looking, as if in recognition, at some painted chickens and a cat. If we anthropomorphise these rats as philosophical creatures, we might imagine them drawing a moral conclusion from the decorative painting they examine. How foolish or arrogant the chickens to be sitting in plain view of the cat. The squirrel, meanwhile, looks out at the viewer, drawing us into the play of looks and layers of representation.

Knorr's works are site-specific. Her prior projects have found their richness in the baggage of particular modes of architecture and sculpture, and of specific cultural institutions. Many works have been set in 18 th and 19 th century British interiors, the territory of Sir John Soane, Lord Burlington, and Robert Adam. 2 Knorr leads us to reflect on our ongoing relationship to the spaces and artifacts depicted, and also on the Enlightenment values that they represent: rationality, order and an elegant austerity on the one hand, and a darker tradition of elitism, exploitation and control on the other. The French context of the Fables gives the work a slightly different emphasis. We are still located in the museum, that is to say in a version of the past as projected by the present. 3 The Musée Carnavalet presents period rooms from different sites and eras in the history of Paris. The photographs in this series are set in the museum's ancien régime interiors. While these rooms serve to display the wealth and magnificence of their original inhabitants, they also attest to an engagement with the key artistic notions of the day. In the case of Demarteau's study, we are looking at a decorative scheme based on a playful slippage between nature and culture, a highly self-conscious art, delighting in its own artificiality at the same time as it mimics certain aspects of the natural world.

In this context, Knorr's sewer rats are vermin, providing an element of abjection. They are as out of place in this painted barnyard as the sound of a cock's crow or the smell of chicken shit. Flattened onto the same plane as their painted rivals, the rats and squirrel add another layer to the Rococo discussion of artifice and illusion, a layer that takes place in contemporary photographic terms. The camera angle used throughout the series helps to draw us into strange identification with the animals. Angling her large format camera up from the floor, Knorr has given us a rat's-eye view, with perspectival distortion optically corrected by tilting the back of the camera. The result is a disconcerting mechanical view that implies a very low, non-human spectator. 4 Using photographic means as well as the skills of a child at play, Knorr recuperates this room for a contemporary reprise of the kinds of conversations about art that might once have taken place within it.

In The Blue Salon Louis XVI , the flavour of the room is neoclassical, but with a decidedly pre-revolutionary twist. While artists during the French Revolution may have seen classicism as the style of republican masculinity and gravitas , artists at the tail end of the ancien régime turned to Greece and Rome for a model of refined simplicity and grace, a kind of feminised classicism. 5 In this interior from the 1880s we see furniture with long slim legs, and a folding screen decorated with grotesques, inspired by the frescoes at Pompeii. In the background hangs a portrait of a female sitter styled with a loose muslin head wrap and informal gown. In contrast to the formal court portraiture of ten years earlier, images like this were designed to reflect a Rousseauian naturalness and simplicity--the kinds of values that led Marie Antoinette to dress up as a shepherdess. Knorr has peopled this room with a family of foxes, a female with two cubs. Poised warily across the bottom of the frame, the foxes criss-cross the picture plane with their glassy gazes. These are not cute Beatrix Potter animal-people, but something more awkward and troubling. Without the foxes, the photograph might be seen as a contemporary document of a historical interior. Their presence charges the room with Knorr's own personality and humour. She has penetrated this historical interior with its highly stylized version of naturalness, and has introduced another layer of un-natural nature.

Staged photography provides a suitable extension of the 18 th century preoccupation with the relationships between nature, culture and the artist's imagination. The digital element of the work gives the photographic artist additional power to master and subdue the index, potentially moving towards painterly ideas. Knorr has turned only recently to digital technology. Like many contemporary practitioners, she now shoots her images on large-format film, and then scans the negatives so that she can tweak and alter. She could use this capacity to make the images more believably illusionistic, to enliven them. But Knorr is clearly not aiming for the photographic realism of wildlife photography. For the most part, the animals appear stiff, even a little clumsy. Visual clues suggest that some of them may have been inserted, repeated, or flipped via digital means. We cannot account for how the pigeons in The Green Bedroom Louis XVI came to be suspended across the space, in an elegant swag of outstretched wings. Without the kind of blurring or anatomical distortion that we expect in photography of moving animals since Muybridge, these pigeons seem decidedly un-photographic. This image is the most dynamic of the series, and also the most mannered. While objects of taxidermy might be able to stay propped up in many of the poses that Knorr depicts, these pigeons have attained their flight through the will of the artist. Their composition, complete with disorienting shadows, transforms a relatively plain room into a swooping rococo composition. In this case Knorr's intervention has one-upped the historical interior.

Aesop's fable of the Thirsty Pigeon offers a counterpoint to Pliny's allegory of painting, in which Zeuxis and Parrhasios compete to create the more illusionistic picture. 6 While Pliny's tale deals with the power of the very skilled artist to trick even his peers, Aesop focuses his attention on those who are fooled. And of course it could be any one of us whose questing desire for an item pictured in a mail order catalogue or internet personal ad leads to humbling disenchantment. Karen Knorr is never out to trick us; she lays all her illusions out before us to be examined. This work, perhaps more that any of her earlier projects, stages illusion not merely as a means but an end, to lead us beyond the consumption of historical images and into an irreverent and questioning engagement with them. In Knorr's work, we are the bystanders with the discretion to identify the illusion, and to keep it separate from lived experience. Still, we enjoy the looking.

These curious photographs address the circumstances in which Knorr finds herself. First, she has arrived rather late at the banquet of history. Many of the grand ideas that attract her are trapped, like flies in amber, within the space of the museum, waiting to be rediscovered. Using staging, technical virtuosity, playful humour and a pinch of deliberate awkwardness, Knorr teases some of the most exalted themes of art history out of the objects of elite material culture and into photographic terms. In doing so, she claims an ambition and importance for photography as a medium capable of such work. She also claims a serious role for herself, a woman artist, reworking spaces that were created by men of power and taste. As in the tradition of fable, animals provide Knorr with a vehicle for exploring human desire, vanity and ambition in a mock serious tone that sparkles with wit.

Aesop's Fables, in a classic English translation by George Fyler Townsend, are in the public domain, and are available online at sources including www.literature.org

2 This aspect of Knorr's work is discussed by Antonio Guzman, "Rewind and Fast-Forward: Photography, Allegory and Palimpsest," in Genii Loci: The Photographic Work of Karen Knorr (London: Black Dog, 2002), p. 11.

3 See David Campany, "Museum and Medium: The Time of Karen Knorr's Images," in Genii Loci , pp. 114-123.

4 Conversation with the artist, 2 September, 2005.

5 For a discussion of the overlap between Neoclassic and Rococo tendencies in 18 th century France see Robert Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth Century Art (Princeton, 1967), pp . 3-10.

6 For a discussion of this motif in Knorr's work see Rebecca Comay's interview with the artist, "Natural Histories," in Genius Locii , pp. 65-6.