|

|

| Photography in Flux 1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018 |

|

|

|

| Should I Do a Photography MA? Source 91, Autumn 2017 |

|

|

|

| Expanded Photography: Persistence of the Photographic PhotoResearcher 26 (2016) |

|

|

|

| Poetic, Magic (Book Review) Source 85, Spring 2016 |

|

|

|

| Situations and Seductions: Mariana Rothen’s Shadows in Paradise Photoworks Annual 22, 2015 |

|

|

|

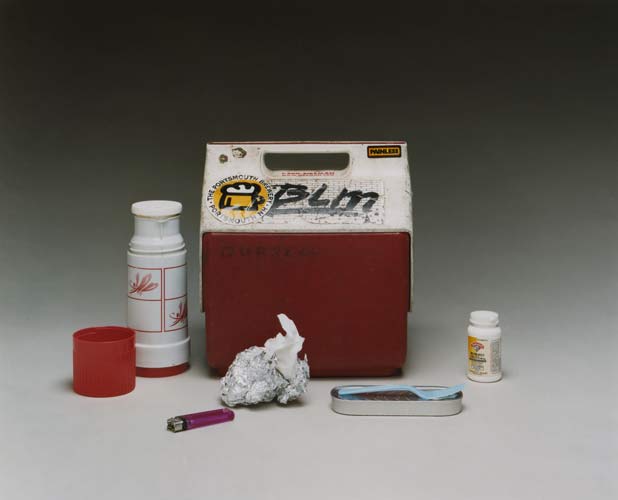

| Conceptual Photography Source 71, Summer 2012 |

|

|

|

| Perhaps When Reproduced Language and Site in Lawrence Weiner's Public Freehold Works ARC14, Summer 2010 |

|

|

|

| Idris Khan: The Collapsed Archive Source 49, Summer 2006 |

|

|

|

| Karen Knorr: Fables Portfolio 42, December 2005 |

|

|

|

| Adam Fuss: Medium as Muse Source 45, Winter 2005 |

|

|

|

| Malerie Marder: The State of Contemnporary Desire Source 44, Autumn 2005 |

|

|

|

| Hannah Starkey: Art's Best Tricks Source 40, Autumn 2004 |

|

|

|

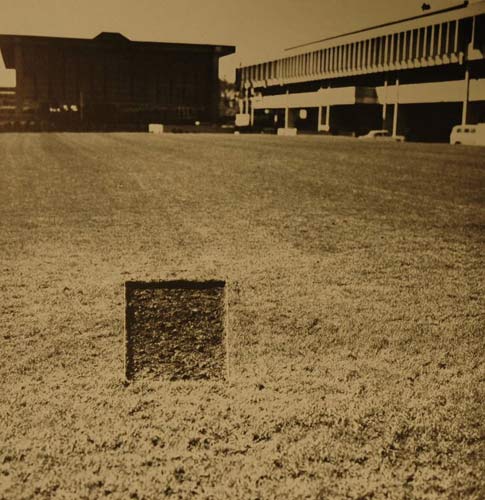

| The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography Afterimage vol. 26 no. 5, March/April 1999 |

1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018

In unpacking contemporary histories of photography as well as the limits and possibilities for the medium it’s clear paradigms are shifting, ideas are on the move.

Photography is emerging from a period of anxiety and mourning. In the mid-1990s, the digital revolution brought photography into a crisis parallel to the one painting suffered in the 19th century, accompanied by the sense that new technologies were usurping its original mission. Photography has suffered many indignities over the past couple of decades. Its truthfulness and timeliness have been challenged from all sides, and the artistic uses of the medium have risked being engulfed by the tsunami of ephemeral digital images. The apocalyptic narrative has been popular. It has sold exhibitions like the “Photography After Photography: Memory and Representation in the Digital Age” (1996), symposia like “Is Photography Over?” (2010) and books such aslike Post-Photography (2014). And yet, here we are: still making, looking at and talking about photography.

From Critique to Complexity

Photographic discourse has splintered since the turn of the millennium. While photographic education and criticism appeared to be consolidating in the 1970s-90s, with their own canon of histories and theories, they are now increasingly fractured. The resulting field of activity is revitaliszed, if difficult to describe in certain terms. In the 1980s and 90s, under the influences of semiotics and post-structuralism, much Anglo-American photographic discourse centered around theories of representation. Photographs were to be regarded as “texts” which, accompanied by various words inside or outside the frame, would allow them to communicate various messages, to perform intellectual work as well as offering aesthetic experience. This model is still dominant but the agenda has broadened. Postmodern theories of representation presupposed that photographic art should offer a model of critique or resistance in relation to dominant structures of power under capitalism. Today many photographers continue to work in explicitly political ways, but not necessarily within the logic of representational critique. In his 2013 book Anywhere or Not at All, Peter Osborne links the eclipse of the paradigm of critical representation to global economic and political changes, and indeed sometimes it seems like photography has fallen into a state of limitless, chaotic consumer choice.

From the perspective of someone who has worked in and around art education for the past twenty-five25 years, I would also link the shift to a more fragmented, eclectic model of photography to a swing of the pendulum away from the hyper-academic art discourse that reached its logical extreme in journals like October or Afterall and in practice-based studio art PhDs. While highly intellectualiszed photography persists, many artists and audiences have turned to other modes of interpretation, other kinds of experience. The visual and visceral have regained ascendance over the textual. Today’s photographic projects might or might not set out to be critical, political, investigative, truthful, authentic, ambiguous, expressive, etc. They might be any combination of these things, offering viewers a set of possibilities for interpretation that may conflict within a single work.

Take a recent image like Edward Burtynsky’s Lithium Mines 1, Salt Flats, Atacama Desert, Chile 2017. On the one hand, this picture operates within a traditional documentary framework – —it provides a previously unseen view of a troubling real-world scenario. At the same time, its candy-bright colours, exquisite sharpness and god’s-eye view make the image as seductive as it is horrifying, the very definition of the sublime as celebrated in Romantic painting. Some critics have condemned the way that Burtynsky aestheticiszes environmental destruction. The photographer, however, embraces his work’s ambiguity. As writer Oliver Wainwright noted in a 2016 Guardian interview, ‘“Burtynsky admits, his images would be equally at home on a Greenpeace poster or the cover of an oil company’s annual report.’” Within Burtynsky’s larger body of work, Lithium Mines 1 is unusual in a number of ways. For a start, unlike most of his other pictures it is not part of a series focusing on a particular industry, as in Oil, Mines or Shipbreaking. At the time of writing, the image appears on the photographer’s website as a teaser for Anthropocene Project, a multi-platform work to include a feature length documentary film, museum exhibition, book, and educational programme. Burtynsky’s stated ambition is to raise public awareness of the Anthropocene, the notion that we have entered an era of mass extinction created by human excess.

Picture vs. Project

While Burtynsky’s previous images all use beauty to attract our attention to the over-exploitation of the landscape, Lithium Mines 1 is especially ambivalent in that lithium is a key component of the re-chargeable batteries used to run “green” technologies such as electric cars, intended to offset the devastating environmental impact of fossil fuels. These points may seem a bit obscure – —that Burtynsky’s series logic has become grander, more abstract and more diffuse, and that the message of this particular picture is more equivocal. The image is, of course, still immediately recognizable as a Burtynsky. Yet these changes belong to broader trends in contemporary photography. Propelled by the internetWeb, striking single images act as representatives of contemporary photographic art. In most cases, however, these images are part of larger projects involving behind-the-scenes research and extra layers of information. Crucially, many contemporary photography projects heighten contradictions and complexity rather than trying to resolve them.

Photographers like Burtynsky, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth bring extreme production values to bear on epic global subjects, creating pictures works at museum scale. While these grand practices dominate major museum retrospectives, the momentum in the field is in practices that are more fluid and idiosyncratic. Take, for example, Cristina DdDe Middel, who turned away from a career in news photography because she was frustrated with mainstream media’s use of photographs to reinforce simplistic stereotypes, particularly about life in the developing world. Her work since has straddled documentary and fiction to provoke flashes of insight. De Middel came to prominence with The Afronauts (2012), a project which riffed on short-lived plans for a Zambian space programme in the 1960s. A fragment of historical fact fueled pictures that are in turns playful, heroic, romantic and fantastical. When a gallery rejected the work as “outside the market” De Middel released it as a book combining the sequence of image with fabricated materials from the period: type-written letters, diagrams, maps and snapshots. The project went on to be exhibited and reproduced internationally, with..

The current boom in photobooks is a reflection of broader changes in the field. The global market for contemporary photography is expanding rapidly but yet gallery careers for individual artists are more competitive and precarious than ever. Photographers at all levels pursue self-generated, self-funded projects and seek their own outlets to show them. Self-published or independent press photobooks provide one of the most reliable ways forare increasingly popular formats for photographers to disseminate projects, so many of which include text as well as imagespictures, and benefit from a slow, considered viewing experience. A series of books on related themes allows a photographer to deepen their engagement with a set of ideas over the course of a career. While DdDe Middel has made projects on several continents, she has used several photobooks to pursue the challenge of representing aspects of African life and culture as an outsider. She followed the The Afronauts with This is What Hatred Did (2015), shot in the Lagos slum of Makoko using Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola’s 1954 novel My Life in the Bush of Ghosts as the inspiration for contemporary staged images. In her latest project, Midnight at the Crossroads (2018), DdDe Middel has worked with her partner Bruno Morais to produce a fictional narrative following the figure of Esù, the trickster deity of the Yoruba people of Western Africa. Re-tracing the slave routes along which African-rooted religions spread across the globe, the images follow Esù from Benin to Cuba, Brazil and Haiti. The photographers weave documentation of modern-day rituals of Santeria and Voodoo with constructed visions of how the deity’s changeable, seductive, chaotic force might be embodied. Read in relation to each other, dDe Middel’s books provide an especially potent set of counter-narratives to western photographic clichés of Africa.

Global Cross-currents

Multi-lingual, DdDe Middel has lived in Spain, the United States, Mexico and the United Kingdom and Brazil. She is one of a number of well-travelled photographers (we might also think of Dafna Talmor, Esther Teichmann, Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, Zanele Muholi or Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin) who have lived and photographed in so many countries that their work becomes transnational, impossible to locate within a single culture of origin.

In becoming more global the photography world has opened to a far broader range of subject positions, historical trajectories and cultural influences. The international circuit of photography art fairs and festivals (including photobook fairs) has recently mushroomed to over 150, with events from Lagos to Lianzhou and from Sydney to São Paolo. These activities provide photographers, curators, gallerists and collectors with access to new practices. In the early 2000s the global photography market foregrounded cultural difference. While the centere of gravity for the photography market lay in the West, non-western identities and locations provided fresh material for eager western collectors, and exotic images sold particularly well. The past decade has seen this dynamic begin to shift. On the one hand, there have been aspects of convergence as the internet makes all styles and periods of photography equally available to photographers all over the world. On the other hand, a burgeoning global infrastructure of photography education programmes and museums encourages photographers to engage more deeply with distinctive local cultures and histories.

A generation of emerging photographers make work for a global audience without necessarily foregrounding cultural identity. When I first saw Me and Me, the self-portrait of a relationship between Yanmei Jiang and Wenjun Chen, I was struck by its universality. A project that launched spontaneously out of the mutual documentation of two photographers between 2007 and 2015, the images were made in Guangzhou, China, but and have relevance for the lives of struggling young creatives in any urban centere. A series of portraits and self-portraits of the photographers evolved into gallery installations and ultimately a multi-part handmade artists’ book including the dual portraits, small diaristic books that Jiang and Chen made about each other, plus excerpts from the social media response they received in response to posts of their evolving project. Crucially, the book’s handwritten Chinese characters were are accompanied by tipped-in English translations; from its conception, this book was intended for an international audience. It hit its target and won a number of awards in places the photographers had never travelled themselves.

The Rise of Curation

Whether arranging images and texts from their own lives into a loose constellation on a gallery wall or into a multi-layered artists’ book, Jiang and Chen are acting as curators of their own content. Ten or fifteen years ago, it was much more common for photographers to work in straightforward series: a set of related prints, usually of uniform size. The looser, more multivalent forms of contemporary art frequently demand that artists take charge of the structure and presentation of their work.

The figure of the curator has become far more important over the past fifteen years. Unsurprisingly, it is curators who have argued for the importance significance of their own contribution, such as Paul O’Neill whose 2007 essay, “The Curatorial Turn: From Practice to Discourse” argues that since the 1960s the exhibitions and writing around exhibitions haves gradually become more influential than art historical or critical writing in contributing new knowledge about art, and that the curator should no longer be regarded as a merely administrative or organiszational figure, but rather as a co-creator of the artwork. Indeed, internationally mobile curators have more power than ever before in identifying which photographers will rise to prominence and which themes and trends will lead the global discussion. More invested in ideas that in mediums, curators have contributed to the erosion of boundaries between specific forms of art, and the prevalence of mixed-media installations. We might also credit them with offering a model of art that is based more on experience than fixed interpretation.

Alongside the rise of the curator, many of the activities of curation such as collecting existing materials, archiving, editing, catalyszing, analyszing and arranging have been taken up by artists. For example, French artist Camille Henrot does not limit her practice by describing it as painting, sculpture, photography or video (although it contains all these forms). She is as likely to include webpages or magazine centerfolds into her work as handmade marks or crafted forms. After its presentation in galleries or museums, each arrangement of materials has an afterlife as a set of installation photographs which preserve a fixed version of the work’s fluid form as a kind of tableau. Henrot may not have a particular investment in photography per se, but there are other artists whose work combines diverse curatorial impulses with a more considered photographic sensibility, including Sara Cwyner, Matt Lipps, Carmen Winant, Daniel Shea and Rosângela Rennó.

Persistence of the Photographic

Henrot’s work, with its disregard for distinctions between mediums, can be contrasted with the work of other artists whose mixed-media work self-consciously retains specific photographic conventions, techniques, materials or concepts. For example, Arash Fewzee makes exuberant large-scale photograms that are displayed either on the wall or draped over frames to produce an installation. Fewzee’s practice could be seen as part of a wave of activity that includes Mariah Robertson, Ellen Carey and Liz Nielsen. While many of these works could be described as “abstract” or “painterly,” Fewzee’s evoke specific reference to the proto-pop paintings that Stuart Davis made in New York in the 1920s-50s. This influence is particularly apt given that Fewzee, an artist from Iran, made the work while studying oion the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The pleasure of Fewzee’s work extends beyond its stylistic resemblance to abstract painting for t. The gestural pictures record playful darkroom performances with photographic materials, and a love-affair with photographic paper and the yellow, magenta and cyan light that pours out of an old-school colour enlarger. In a similar vein, there are many artists now working at the boundaries between photography and sculpture, moving image, installation, performance, etc. for whom photography is not just a means to an end, but a key part of the work’s meaning and affect. Some artists leave the context of photography markets and institutions to be part of the (potentially more lucrative) field of contemporary art. Others, significantly, prefer to remain within the context of photography to participate in its particular dialogues and communities.

From Sense to Sensation

The vast majority of digital photographs never take material form as prints. Paradoxically, however, the omnipresence of screens and disembodied digital images has triggered a renewed interest in materiality. The last decade has seen a conspicuous revival of processes with distinctive surface properties: silver gelatin and analogue chromogenic prints, alternative non-silver processes and unique images like Fewzee’s photograms. Some dealers now go out of their way to call certain works “hand prints” to underline the craft that has gone into their making. There has also been a rise of photographic works that pursue senses other than pure vision, with pictures and installations that explore physical scale or evoke touch with reference to texture, temperature or viscosity.

Anna Skladmann’s The Man with the Midas Touch: A Botanical Index of Narcissus (2017) includes images of thirty30 prize-winning narcissus flowers. The blooms have been submerged in various liquids and placed upon the bed of a flatbed scanner. The resulting colour prints have the sharpness and detail we might expect from a large-format photograph, infused with a visceral strangeness. Gooey and squashed, the flowers have an optical and tactile excess. The distance and point-of-view of an ordinary lens-based photograph underpin the sense that the image is a re-presentation, a considered take on the thing seen. Scans are more direct, stupider. Scanners do not resolve a view into western perspective but merely move across a surface to record its detail flatly. A scan is thus unmediated presentation. We might expect digital technologies to inspire artists to make futuristic, cerebral photographic work. But artists like Skladmann are just as likely to use digital means as part of a current interest in brute matter. The title and texts which accompany the project evoke a conceptual subtext, but the impact of even a single picture in the gallery space is strikingly physical.

Fluid Boundaries

Artist and theorist Victor Burgin has written about the continuities between digital and analogue modes of photography. An artist like Skladmann may use a scanner to make images of unsettling flatness, but in most cases advanced digital technologies perpetuate traditions of perspectival picture-making that go back to the Middle Ages. At the same time, new technologies demand new literacies. Artists such as Erica Scourti, Amalia Ulman and Petra Collins make use of the iInternet’s potential as a medium as well as a platform, and photographers are just beginning to explore the dynamics of the algorithms pre-built into contemporary imaging technologies and of images that are globally networked at the instant that they are produced.

The current climate of eclecticism give photographers permission to cross ever more fluidly between analogue and digital modes, between photographic genres, between artistic mediums and between commercial and personal work. A period of uncertainty has short-circuited some familiar photography career paths, while opening up new ones. Over the past ten years, 1,000 Words has traced and contributed to this rich, changing field. In the selected projects of the past decade we can clearly perceive a renewal. Paradigms are shifting, ideas are on the move.

Images Discussed

1. Edward Burtynsky, Lithium Mines 1, Salt Flats, Atacama Desert, Chile, 2017. Courtesy: the artist and courtesy Metivier Gallery, Toronto

2. From Cristina DDe Middel and Bruno Morais, Midnight at the Crossroads, 2018. Courtesy: the artists (i.e. image has no individual title—I double checked)

3. Yanmei Jiang and Wenjun Chen, Me and Me, 2015. Courtesy: the artists (Wenjun usually gets listed first, either for alphabetical or sexist reasons, so let’s but Yanmei first this time!)

4. Camille Henrot, The Pale Fox, installation view, Chisenhale Gallery 2014. Commissioned and produced by Chisenhale Gallery in partnership with Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen; Bétonsalon – Centre for art and research, Paris and Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster. Courtesy kamel mennour, Paris and Johann König, Berlin. Photo: Andy Keate. © ADAGP

Camille Henrot, (I’m not sure exactly which version of The Pale Fox you ended up with, so you’d better check the title line)

5. Arash Fewzee, Untitled, 2017. Courtesy: the artist and the Rubber Factory

6. Anna Skladmann, Mondragon, from the series ’s The Man with the Midas Touch: A Botanical Index of Narcissus, 2017. Courtesy: the artist