|

|

| Photography in Flux 1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018 |

|

|

|

| Should I Do a Photography MA? Source 91, Autumn 2017 |

|

|

|

| Expanded Photography: Persistence of the Photographic PhotoResearcher 26 (2016) |

|

|

|

| Poetic, Magic (Book Review) Source 85, Spring 2016 |

|

|

|

| Situations and Seductions: Mariana Rothen’s Shadows in Paradise Photoworks Annual 22, 2015 |

|

|

|

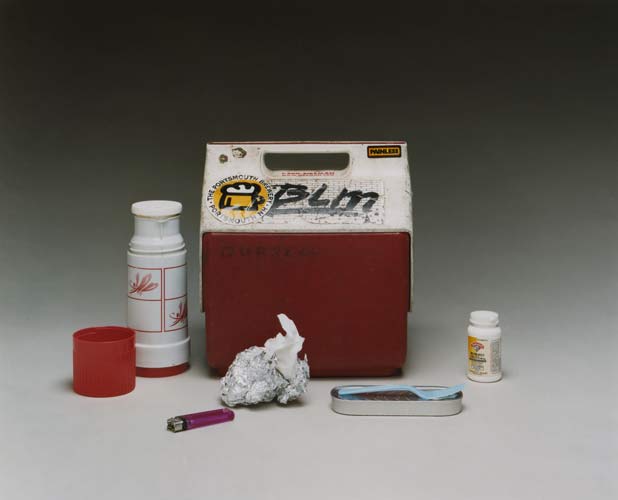

| Conceptual Photography Source 71, Summer 2012 |

|

|

|

| Perhaps When Reproduced Language and Site in Lawrence Weiner's Public Freehold Works ARC14, Summer 2010 |

|

|

|

| Idris Khan: The Collapsed Archive Source 49, Summer 2006 |

|

|

|

| Karen Knorr: Fables Portfolio 42, December 2005 |

|

|

|

| Adam Fuss: Medium as Muse Source 45, Winter 2005 |

|

|

|

| Malerie Marder: The State of Contemnporary Desire Source 44, Autumn 2005 |

|

|

|

| Hannah Starkey: Art's Best Tricks Source 40, Autumn 2004 |

|

|

|

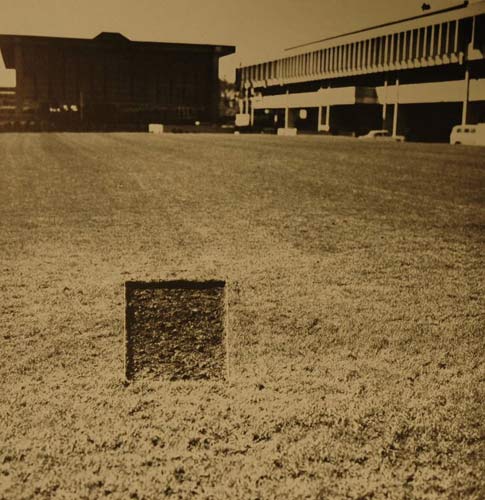

| The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography Afterimage vol. 26 no. 5, March/April 1999 |

Timothy Taylor Gallery

9 September-14 October 2005

Source 45, Winter 2005

Adam Fuss is known for his artistic use of historical processes and for making cameraless images: photograms (most famously of a dead rabbit and its innards) and pinhole pictures. The works refer to the natural world or to ephemeral effects, and usually involve a tension between abstraction and figuration. This is Fuss' first solo show in Britain. Including works from four different series, produced between 1990 and 2004, the exhibition is too small to count as a mid-career retrospective, but certainly provides an overview of the major themes and strands of technical exploration to be found in his work.

The first room of the gallery features Untitled (1990) a series of eight 20" x 24" photographs. These works are unusually conventional for Fuss, in that each was shot with a camera and printed on regular black and white paper. The twist lies in the fact that the images initially appear to be completely black. These pictures create an unusually demanding viewing experience, akin to looking at an Ad Reinhardt painting. Only after staring extensively into the surface of the prints--heavy with silver and ever-so-slightly shimmery--do viewers discern that every rectangle contains the head and narrow torso of a naked boy. Each stares out of the frame with slightly different expression: defiant, wary, yearning, frightened. These boys could stand as a metaphor for the voices or personalities that lie latent within us (a reading supported by the dull reflection of oneself in the glass that is evident long before the boys are visible). This is most effective when their expressions are most blank. One or two have puppyish, piercing gazes, pushing me to read them more literally, as weirdly aestheticized victims of torture or abuse.

The exhibition's inner room offers an entirely different perceptual experience. In the series Ark , 2003, Fuss has used the polished silver-coated plates of the daguerreotype process, without a camera, to document the circular waves rippling out from drops of water. These mirrored surfaces, pink or blueish silver, depending the angle of view, embody a kind of watery sublime. Tiny star-shapes mark the moment of initial impact, and target rings trace the aftershocks. Each work has been floated in a perspex frame, with these reflective surfaces contributing to a dizzying layering of reflections. The spotlit daguerreotypes reflect each other, and the viewer within the room, creating a magical, floating installation. There are reasons why the daguerreotype process fell out of favour in the 1850s; the metal plates are expensive, delicate and--given that each is developed in boiling mercury vapour--dangerous to produce. Fuss turns these drawbacks to his advantage, using the process to transform fleeting effects into permanent, unique objects that are literal and abstract at the same time.

The dark silver prints and the daguerreotypes make highly mannered use of photographic process to produce their own viewing conditions. The middle room contains two works in which the technique seems rather to border on gimmickry. Untitled , 2003 is a pigment print of a butterfly chrysalis, as captured in the eerie glow of a digital flatbed scanner. The image is large and lovely, with a pale fleshy colour reminiscent of human skin, but seems much more literal than any of the other works in the show, its symbolism heavy-handed. Perhaps in series, this piece would gain more depth. For Untitled 2005, Fuss has sprinkled a large horizontal sheet of silver paper with some kind of powder, and then exposed it to the light while letting a live snake slither about on its surface. The result is an expressionistic mess of darks and lights, a pattern that crosses Jackson Pollock with snake skin. With its combination of artistic control and animal randomness, this seems rather contrived. As is often the case with Fuss' work, I ask myself whether any picture made using this technique would be equally valid and equally interesting?

In interviews, Fuss places emphasis on the associative, metaphorical power of his images. He likes words like "oneness" and "revelation." As far as he is concerned, the technical aspect is the least compelling part of his project. In fact, he is very concerned that audiences might pigeonhole pieces by process and then fail to look and think for themselves. For my part, I find the grounding of the works in historical techniques gives them a seriousness and a visual, material intensity often lacking in contemporary photography. And I often find the form of the works to be more compelling than their ostensible content.

In some ways Fuss is a latter-day pictorialist, turning to outmoded techniques--as Stieglitz or Steichen turned to the platinum print or gum bichromate--in order to heighten the artistic and expressive impact of his images. Like the pictorialists, Fuss uses alternative processes to transcend photographic literalism and muse upon more metaphysical concerns: creation, destruction, transformation, transcendence and inner states of mind. Even in the 1890s, the pictorialists struggled to sublimate the visual stuff of the world into photographic works of art, and often found that a tiny detail, too literal or too crude, could tip an otherwise exquisite image into sentimentality or pretention. For the most part, Fuss uses abstraction as his ally to stay on the safe side of this line. At their best his works have an otherworldly presence and conviction that operates on a viewer in a completely different way from standard photographic representation.