|

|

| Photography in Flux 1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018 |

|

|

|

| Should I Do a Photography MA? Source 91, Autumn 2017 |

|

|

|

| Expanded Photography: Persistence of the Photographic PhotoResearcher 26 (2016) |

|

|

|

| Poetic, Magic (Book Review) Source 85, Spring 2016 |

|

|

|

| Situations and Seductions: Mariana Rothen’s Shadows in Paradise Photoworks Annual 22, 2015 |

|

|

|

| Conceptual Photography Source 71, Summer 2012 |

|

|

|

| Perhaps When Reproduced Language and Site in Lawrence Weiner's Public Freehold Works ARC14, Summer 2010 |

|

|

|

| Idris Khan: The Collapsed Archive Source 49, Summer 2006 |

|

|

|

| Karen Knorr: Fables Portfolio 42, December 2005 |

|

|

|

| Adam Fuss: Medium as Muse Source 45, Winter 2005 |

|

|

|

| Malerie Marder: The State of Contemnporary Desire Source 44, Autumn 2005 |

|

|

|

| Hannah Starkey: Art's Best Tricks Source 40, Autumn 2004 |

|

|

|

| The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography Afterimage vol. 26 no. 5, March/April 1999 |

Source 71, 2012

When photographs appear in the conceptual art of the 1960s and early 70s they are usually paired with words in the form of titles or text panels. We might think of Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) or John Baldessari’s Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts) (1973), in which language and image are inseparable, repeating the same idea in two different ways. Works like these locate most of their pleasure in the mind; they are thought experiments carried out in the space between words and pictures. They are completed in the viewer’s imagination. The actual photographs are banal so as not to detract attention from the (often rather dumb) idea as art, and also to convey a certain seriousness of intent. Many first-generation conceptual art works are messier than these examples. They involve pseudo-logical systems that do not actually make much sense, and/or images that fail to match the text that they accompany. In most cases, however, the central push and pull between word, image and idea is the same.

The role of photography changed in the postmodern photography of the 1980s. Artists like Richard Prince, Jeff Wall or Candida Höfer clearly have concepts in mind, but they allow their images much more visual fullness and pleasure in themselves. Titles (in many cases Untitled) are important, but ideas are mostly carried elsewhere. Many artists of this generation—Wall in particular—have theorized their own work extensively, and at the same time the 80s and 90s saw a boom in the institutional discourse around photography. While earlier conceptual work had been too obvious to require much explanation, these works invited interpretation. Critics, curators and art historians took on a greater proportion of the work of explaining the conceptual content of photography. Drawing on poststructuralist theory, these figures frequently interpreted photography in relation to critiques of power. Art schools, museums and art magazines set out to train viewers apply these critical allegories for themselves. The popularity of photography during this period, however, clearly relied not just on its intellectualism, but also on its visual intensity, the strength of the photographs as pictures.

Contemporary photographers operate in an environment that is simultaneously rigid and permissive. On the one hand, the majority are trained at art schools where they are required to provide a clear conceptual rationale for their work, especially at BA level. On the other hand, their work becomes increasingly eclectic, ambiguous, and resistant to interpretation at MA level and after graduation. It appears that artists and audiences today have an increasing appetite for interpretive openness.

Photography today may be conceptual in all sorts of different ways. It may provide a self-conscious twist on a traditional genre of picture making such as portraiture, landscape or documentary. It may rely on a conceptual system for its making. It may have a pointed relationship to an event, a performance, or a work carried out in another medium. It may employ any combination of these strategies. The concepts underlying the work may be made explicit within the work through titles or text panels, they may be articulated externally via press releases, catalogue essays, etc., or they may rely on viewers’ insider knowledge.

We are now frequently confronted with works in which a key aspect of the conceptual premise is partially withheld. For example, Thomas Demand’s photographs of sculptural reconstructed scenes draw on highly loaded photographic source material that may or may not be identified. Why withhold information that explains the meaning behind an image? Some of the coyness of contemporary art is elitism, stemming from a desire to create an aura of exclusivity around the work, a reward for those who take the trouble to become insiders. But there are other important reasons to resist conceptual clarity. Partly as a backlash against prescriptive postmodern readings, and partly in response to contemporary theorists such as Jean-Luc Nancy, artists are beginning to consider images not just as springboards to interpretation, but also as concentrations of sensation to be experienced before and outside interpretation.

This is not a new idea. In his 1931 essay “A Short History of Photography,” Walter Benjamin describes every photograph as having a remainder or surplus that the photographer/artist cannot account for. Benjamin regarded accidents, the fragments of the here and now that enter every photograph, as providing the sparks that illuminate images and captivate the viewer. In other words, photographs are images with a special relationship to the world. However much artists may load them up—with content, with intent, with concepts—they will remain on some level resolutely, perversely visual. Contemporary art photography is currently embracing this notion. Photographers are at liberty to draw on the precedents of earlier conceptual and postmodern practices, as well as the theories that framed them, but they also have the freedom to wear their conceptual influences lightly, to produce works that cannot be pinned down fully in words.

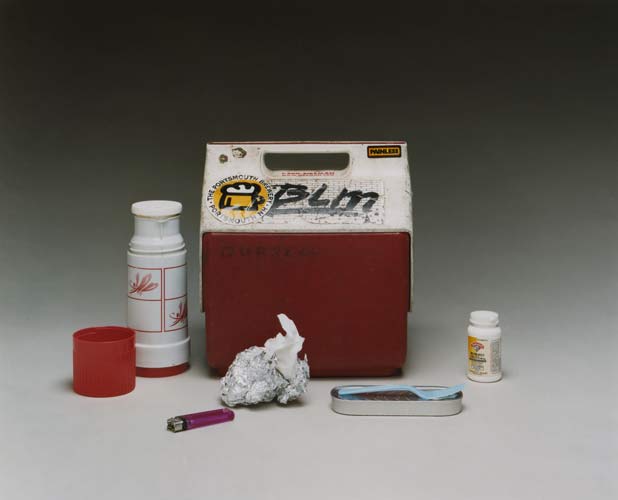

For an example of an artist who welcomes this kind of contingency into her work, we might look at Sharon Lockhart, whose practice is located partly in photography, partly in film. Her work is based on extensive research (another common feature of contemporary conceptual art). Her eclectic subject matter has ranged from radical Japanese flower arranging to ethnography in the Amazon Basin, from a scene in a François Truffaut film to American workers’ lunchboxes. The resulting projects have layers of meaning, some of which are available to the viewer via external texts like wall labels and reviews. At the same time, Lockhart’s photographs and films have a compelling presence. We do not necessarily need to be familiar with the work’s conceptual subtexts in order to be struck by its affect, what it does to us when we experience it in person.

Some writers have described the looseness of contemporary conceptual photography as reactionary, as a betrayal of photography’s potential to be a socially and politically engaged art form. On the contrary, artist/photographers are exploring a richer diversity of political practices than ever before. At the same time, the ambiguity and eclecticism of much photographic work could be understood as confirming that art is not just a set of didactic cultural objects to be studied, but also a set of aesthetic experiences whose value and meaning overflow explanation.