|

|

| Photography in Flux 1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018 |

|

|

|

| Should I Do a Photography MA? Source 91, Autumn 2017 |

|

|

|

| Expanded Photography: Persistence of the Photographic PhotoResearcher 26 (2016) |

|

|

|

| Poetic, Magic (Book Review) Source 85, Spring 2016 |

|

|

|

| Situations and Seductions: Mariana Rothen’s Shadows in Paradise Photoworks Annual 22, 2015 |

|

|

|

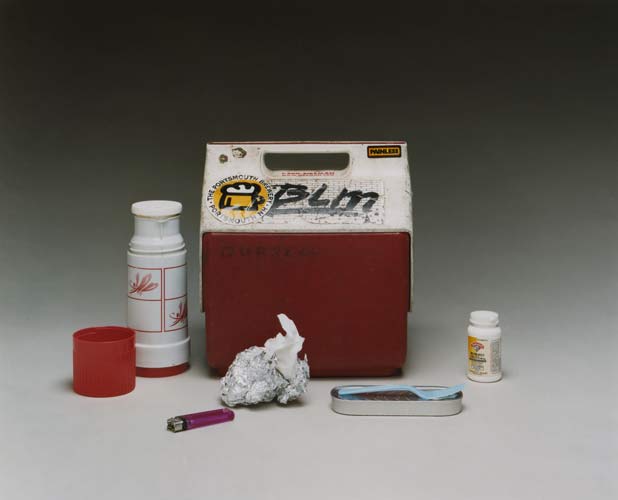

| Conceptual Photography Source 71, Summer 2012 |

|

|

|

| Perhaps When Reproduced Language and Site in Lawrence Weiner's Public Freehold Works ARC14, Summer 2010 |

|

|

|

| Idris Khan: The Collapsed Archive Source 49, Summer 2006 |

|

|

|

| Karen Knorr: Fables Portfolio 42, December 2005 |

|

|

|

| Adam Fuss: Medium as Muse Source 45, Winter 2005 |

|

|

|

| Malerie Marder: The State of Contemnporary Desire Source 44, Autumn 2005 |

|

|

|

| Hannah Starkey: Art's Best Tricks Source 40, Autumn 2004 |

|

|

|

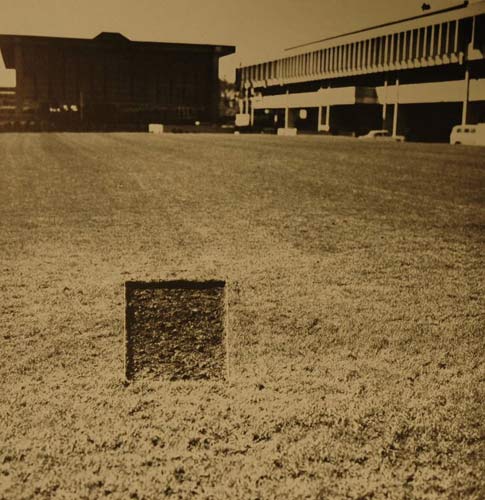

| The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography Afterimage vol. 26 no. 5, March/April 1999 |

Photo-poetics by Jennifer Blessing

Photography Is Magic by Charlotte Cotton

Source 85, Spring 2016

The first thing to say about these two books is that they are both highly desirable objects if you like semi-abstract photography loaded with conceptual subtexts and coded as contemporary art (documentary purists need read no further). These are images that refer more to other images than to the world, photographs that owe as much to the studio and to software as they do to the darkroom. Charlotte Cotton’s elegant Aperture paperback Photography Is Magic is a medium-sized coffee table book with 327 full-page colour illustrations of recent work by more than 80 artists. It is the most comprehensive collection to date of work in this mode. Jennifer Blessing’s Photo-Poetics: An Anthology is a more unusual proposition. While the images are drawn from the checklist of a show at the New York Guggenheim (running from November 2015-March 2016), the slender, tape-bound volume looks more like a small-edition artist’s book than an exhibition catalogue. Inside, text is interspersed and evenly weighted with images by 10 artists. The goal of Blessing’s book is to immerse the reader/viewer as deeply as possible into the works.

There is a good deal of overlap between the photographic practices included in the two books. Leslie Hewitt, Elad Lassry, Erin Sherriff and Sara VanDerBeck feature in both, and many artists that appear in one book could easily have fit into the rationale of the other. Blessing’s selection leans slightly more towards still life, and practices that make overt reference to books. She includes two video works and a couple of slide projection loops. Some of Cotton’s choices are more exuberantly visual, making explicit reference to painting, fashion or advertising. The main difference lies in the way that the two writers characterise the work, both in the terms they choose to describe it, and the modes of writing that they use to accompany it. For Blessing, this kind of art crucially shifts the way photography is understood. She defines photo-poetics as “an art that self-consciously investigates the laws of photography and the nature of the photographic.” Blessing regards this project as rooted in the conceptual art of the 1960s and 70s and in the “Pictures” generation of 1980s postmodern photography. As the Guggenheim’s Senior Curator for Photography, Blessing argues that these new works belong in the canon of both photography and contemporary art.

In contract to Blessing’s art historical framing of the work, Cotton’s main emphasis is on the wonder this kind of photography can generate, and on the power such images have to ignite the viewer’s imagination. Her central metaphor is to close-up magic—the kind of intimate prestidigitation that experienced magicians do for each other and for friends. In both the magic and the photographic images, Cotton argues, the trick is completed in viewers’ own minds. Cotton traces precedents for this photographic work to Duchamp, the cubists and 80s Simulationists, but she characterizes the new works as “misdirections” or “reanimations” of past impulses. Her focus is on their affect in the present and the ways that they redirect our attention in relation to contemporary visual culture.

The two books make very different proposals about how to write about this kind of work, implying different ways of looking at art. An independent curator, who has spoken in various contexts about her ambivalence towards photographic institutions, Cotton avoids an academic approach. While her footnotes carry a stream of intriguing quotations from sources ranging from philosopher Vilém Flusser to curator Nicolas Bourriaud and new media theorist Lev Manovich, she does not develop her points explicitly in relation to them. Cotton argues that old-fashioned modes of interpretation may no longer be necessary since the current moment offers, “unprecedented compatibility and transparency between viewers and artists.” She opens her book with a substantial (18 page) introductory essay, and closes with single paragraph statements by each of the artists. The experience of the pages in between is an unbroken flow of images, 2-7 pages per artist, with small captions of maker, title, date and medium as the only additional information. The argument here is that these pleasurable works are primarily to be looked at, and that you, the viewer, should feel empowered to enjoy them with minimal intervention.

Although Blessing also makes a strong pitch for the role of the individual’s response to the work, she sets herself up as a kind of special-case viewer. Sandwiched between very short general sections entitled “Introductions” and “Afterwords,” she gives each of the 10 artists the same treatment: a short descriptive essay addressing a single image or project, followed by a more traditional single-paragraph catalogue entry (by Guggenheim Assistant Curator Susan Thompson). Blessing’s essays are written in a subjective, reflective tone. With a close attention to the specific affect of particular image fragments, surfaces, frame choices, etc., as well as to aspects of each project’s conceptual premise, her writing avoids closure. At the close of a rhapsodic, phenomenological description of Hewitt’s Riffs on Real Time, Blessing even writes, “I thank Leslie Hewitt for her careful attention to this text, and for encouraging me to resist deterministic reading of her work.” In sharp contrast, Thompson’s short summaries have the brisk, authoritative tone we expect from museum labels, tying each artist’s project into a tight conceptual bundle. For example, Thompson characterizes Leslie Hewitt’s project as follows: “Hewitt’s references to the seventeenth-century Dutch still life tradition present a postcolonial critique of the economic infrastructure predicated on the movement of labor, food, and the material objects in early capitalism that produced the genre.”

Both these books discuss photographic art that operates on at least two levels; it is formally seductive enough to please a broad range of viewers, while at the same time offering deeper biographical backstories, critical allegories and conceptual rationales. Charlotte Cotton makes claims for the ready accessibility of such work, implies, indeed, that we might prefer not to think about what happens beneath the surface. Certainly, one may enjoy the images in Photography is Magic without further information. But I think it is misleading of Cotton to suggest that a one-paragraph artist’s statement can give the viewer/reader all the information they need. Audiences often enjoy learning how a trick was done as much as they enjoy the illusion. Blessing’s book offers a much better-rounded sense of what kinds of creative and intellectual labour might have gone into the images and what kinds of attention and prior knowledge might be valuable in unpacking them, if that is what a viewer chooses to do. Whether you prefer the poetic or the magic approach, both are timely, important books developing the conversation around a fast-growing area of photographic practice.