|

|

| Photography in Flux 1000 Words: 10 Years (print edition), 2018 |

|

|

|

| Should I Do a Photography MA? Source 91, Autumn 2017 |

|

|

|

| Expanded Photography: Persistence of the Photographic PhotoResearcher 26 (2016) |

|

|

|

| Poetic, Magic (Book Review) Source 85, Spring 2016 |

|

|

|

| Situations and Seductions: Mariana Rothen’s Shadows in Paradise Photoworks Annual 22, 2015 |

|

|

|

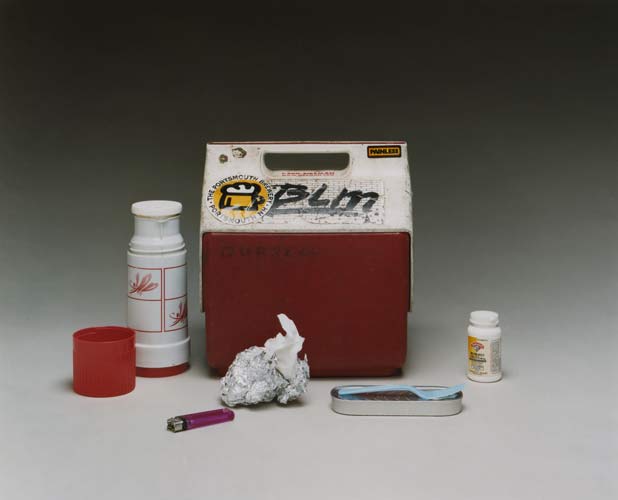

| Conceptual Photography Source 71, Summer 2012 |

|

|

|

| Perhaps When Reproduced Language and Site in Lawrence Weiner's Public Freehold Works ARC14, Summer 2010 |

|

|

|

| Idris Khan: The Collapsed Archive Source 49, Summer 2006 |

|

|

|

| Karen Knorr: Fables Portfolio 42, December 2005 |

|

|

|

| Adam Fuss: Medium as Muse Source 45, Winter 2005 |

|

|

|

| Malerie Marder: The State of Contemnporary Desire Source 44, Autumn 2005 |

|

|

|

| Hannah Starkey: Art's Best Tricks Source 40, Autumn 2004 |

|

|

|

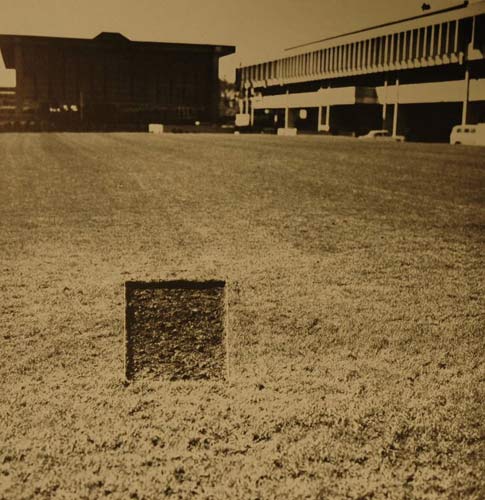

| The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography Afterimage vol. 26 no. 5, March/April 1999 |

Photoworks 22, 2015

A glamorous blonde—let’s call her ‘Blondie’—is hiding out at a run-down old house. She is fully made up like a 60s French film star, but there is something off-kilter about her appearance: in some pictures her hair looks like a doll’s wig. She’s got one outfit that she wears in various permutations: a slip, a cotton dress, a stripy sweater and a leather trench coat. Blondie has time to kill. She sits around smoking, staring into the middle distance or looking out of a broken window. She doesn’t turn on the TV. She holds a book in her lap but doesn’t read it. She picks up the phone but she doesn’t talk on it. She is waiting for something to happen, a call or the arrival of a visitor. From the quality of her gaze, she seems kind of depressed, maybe even afraid. She sits on the front stoop with her head in her hands. She lies on the brown shag carpet staring at the contents of a spilled ashtray. And she may well have reason to be afraid. In one frame she is prone, as if struck down, outside the front door, with a battered pram overturned beside her. But she’s the one with the gun, held close to her chest as she smoulders behind a lace veil. A final image closes in on her face, veiled by hair now rather than lace, and washed out by bright sunshine, as she looks right out at us.

This version of the story is my own. You might make something else of it, and Marianna Rothen’s photographs invite you to do so. For a photograph to read as a compelling narrative it has to have something mysterious about it. If all were revealed, the image would read as a flat depiction, a showing rather than a telling. The best narrative photographs offer a central ambiguity, while crucially inviting the viewer to connect with the characters or situations depicted. Rothen’s Blondie is just the sort of seductive cipher to draw us into this process.

Rothen is unusual among narrative photographers in that she actively varies the narrative situation, the implied positions of the author, characters and viewer. Some of the photographs in this series, like Risky Business, show us a scene as if viewed by an impersonal, external narrator. Others, like Rosebud and Ashtray, invite us to perceive the story world through the eyes of the central character. She does not narrate per se, but serves to guide our looking with her looking. Still other images, like Curtain, Backstabber and Still Life, are framed to place our gaze in a threatening relationship to the character. They imply a voyeuristic, predatory role for us, the viewers. We could think of these as being narrated in the second person, as in ‘You are standing here’. In a fourth category of images, including Donkey Skin and Cowboy 4, Blondie looks us straight in the eye, breaking the frame of the image to make contact with us. This is the closest she comes to serving as a first person narrator rather than just a protagonist. This narrative instability produces a cinematic intensity and allows the series to unfold without feeling predictable or illustrative.

A mini series called Shadows in Paradise, these 13 images make up a chapter in a larger body of work currently in progress. Like much of Rothen’s previous work (in which Blondie occasionally appears), they take place in an all-women environment and present post-war Western norms of beauty in a playful mash-up. Rothen is part of a generation of female photographers who belong as much to the internet as the gallery. Her New York gallery, Steven Kasher, recently included her in an exhibition of nudes by photographers including Olivia Locher, Shae DeTar and Amanda Charchian—all active bloggers with tens of thousands of Instagram and Tumblr followers. For this generation of artists, selfies, interviews, social media presence and viewer comments are paratexts informing the interpretation of their work. They offer up aspects of their own subjectivity as part of a shared project: to recuperate the visual pleasures of the female form with a 21st century aesthetic.

Artists working in staged photography sometimes distance themselves from fashion by making their work larger and sharper, more banal or more spectacularly cinematic than we usually expect fashion editorial to be. Rothen prints most of her images at relatively small scale, shifting fluidly between black and white and colour, and mixing sharp images with atmospherically blurred ones, thus allowing her work to overlap with the visual tropes of fashion. Parallel to the way song lyrics can lack sense in terms of grammar and reference, but still pull on the emotions when paired with melody, the best fashion images create affect from elements that do not add up on their own. A bra strap or a flutter of false eyelashes may produce a flash of desire, or a vivid sensory projection of what it feels like to be in that scene, in that skin. A former model herself, Rothen has an insider’s knowledge of how images can generate sensation, projection and identification.

Rothen often includes books in her photographs. Their titles provide atmospheric epigraphs for the images, and sometimes add layers of reference. Shadows in Paradise refers to the title of a novel by Erich Maria Remarque (best known for All Quiet on the Western Front). Published after the author’s death, the novel explores the lives of European émigrés after the World War II. Like Remarque himself, the German protagonist has a beautiful Russian girlfriend, a former model, with whom he pines for a pre-war Europe to which they can never return. The photographs in Rothen’s series have some of the nostalgic melancholy of the novel, but are set closer to the book’s 1972 publication date than its late 1940s setting. The fractured viewpoint of the photographs echoes the inconsistencies of the novel, which some critics consider to be an unfinished draft. In the first image of the series, a copy of the novel lies across Blondie’s lap, emphasising the jacket photograph of Remarque himself. A figure of high romance, Remarque had affairs with Hollywood legends including Hedy Lamarr, Dolores del Rio, Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo. Although Rothen’s photographs are not an illustration of his text, they deepen in relation to his brooding presence.

Does it matter who the model is for Blondie? Would it shift the way we perceive the story if she were someone significant, even the artist herself? In the set of Cowboy images with Blondie wearing the veil, the viewer is presented with a visage all the more alluring for being partially obscured. In these images, Blondie is simultaneously herself as a character and the object of the photographer’s—and our—gaze. Shifting the narrative situation from picture to picture, Rothen creates a layered masquerade. Actress, model and protagonist, Blondie is also voyeur, predator and prey.